Design & Print Tips

DPI vs PPI: The Confusion That’s Been Driving Designers Crazy for Decades

You know that moment when someone asks you about “DPI” and you internally cringe because you know they probably mean PPI? Yeah, we’ve all been there. After years of explaining this to clients, friends, and even fellow designers, I’m convinced this is one of the most misunderstood concepts in our industry.

The Real Deal: What DPI and PPI Actually Mean

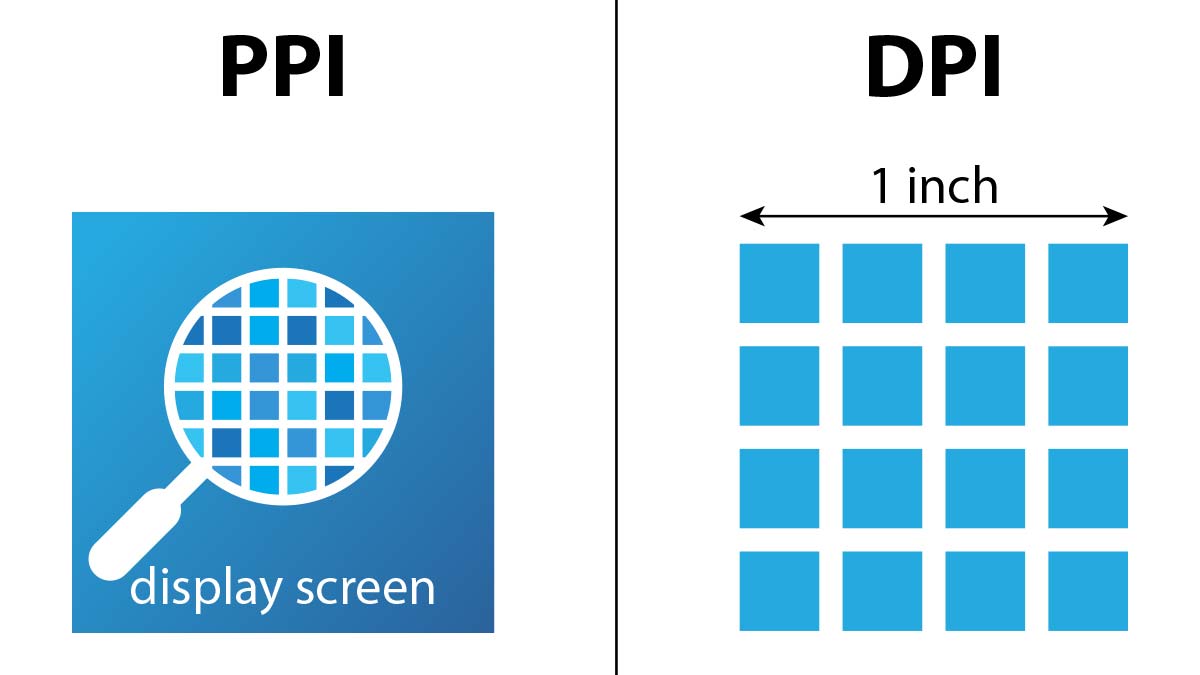

DPI (Dots Per Inch) refers to how many ink dots a printer can physically lay down in one inch. It’s all about printing – think of your office printer or that fancy large-format plotter at the print shop.

PPI (Pixels Per Inch) measures how many pixels fit into one inch on a digital display. Your monitor, phone screen, tablet – they all have PPI ratings.

Here’s the kicker: they’re not interchangeable, despite what half the internet seems to think.

Why Everyone Gets This Wrong

Back when I started designing in 2014, I noticed something funny. Clients would send me “low DPI images” for their websites. But here’s the thing – websites don’t have DPI at all! They only care about pixel dimensions and file size.

The confusion comes from Adobe Photoshop and other design software. When you create a new document, you see both “Resolution” and a dropdown that says “pixels/inch.” This setting is purely metadata – it doesn’t change how your image looks on screen.

Try this experiment: Create two identical 1000×1000 pixel images, one at “72 DPI” and another at “300 DPI.” Open them both on your computer. They’ll look exactly the same size because your monitor doesn’t care about that metadata 😃

When DPI Actually Matters (Spoiler: Only for Printing)

DPI becomes crucial when you’re sending files to print. Here’s my go-to rule after years of print projects:

• 300 DPI minimum for high-quality prints (business cards, brochures, magazines) • 150-200 DPI works for large banners viewed from distance

• 600+ DPI for fine art or detailed illustrations

Pro tip: Always ask your print vendor what they prefer. I’ve learned this the hard way – some specialty printers have very specific requirements.

The Digital World Lives in Pixels, Not Dots

For everything digital, forget DPI exists. Focus on these instead:

Screen Resolution and Pixel Density

Your iPhone has roughly 460 PPI, while most desktop monitors sit around 72-110 PPI. This is why the same image can look crisp on your phone but pixelated on a large monitor.

Responsive Image Sizes

I always prepare web images at 2x the display size minimum. So if an image appears 400px wide on a website, I’ll export it at 800px wide. This handles most high-density displays beautifully.

Common Scenarios That Trip People Up

“My logo looks blurry on the website!” This isn’t a DPI problem – you need a larger pixel dimension or an SVG file.

“The printer says my image is too low resolution!” They mean you need more pixels and the right DPI setting for their workflow.

“Should I save web images at 72 DPI or 300 DPI?” Honestly? It doesn’t matter for web display. Save your bandwidth and go with 72 DPI, but focus on getting the pixel dimensions right.

My Personal Workflow (What Actually Works)

After dealing with countless print disasters and pixelated web images, here’s what I do:

For Print Projects:

- Work at 300 DPI from day one

- Keep original high-res files separate from web versions

- Always send a test file to the printer first

For Digital Projects:

- Ignore DPI completely

- Focus on pixel dimensions and file optimization

- Use vector formats (SVG) whenever possible for logos and icons

The Bottom Line

DPI = Printing. PPI = Screens. That’s it.

Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise, and don’t feel bad if you’ve been mixing these up – even seasoned designers get tripped up sometimes. The important thing is understanding when each one matters for your specific project.

IMO, the industry would be better off if software stopped showing that confusing “DPI” field for digital projects altogether. But until that happens, at least now you know the real story behind this decades-old confusion.

Got questions about resolution for your next project? The key is always knowing where your final output will live – on screen or on paper. Everything else falls into place from there.